The Landmark Series has a new web site

The Landmark Series is the most accessible and detailed set of classics editions ever published of the great works of Thucydides, Herodotus, Arrian and Xenophon. The series editor Bob Strassler is a board member of the Reading Odyssey. The Landmark collection now has its own web site here: http://www.thelandmarkancienthistories.com/

Alexander the Great Discussion Series Part 3

Interested in Alexander the Great? Join us for:

– Weekly dialogue between historians Paul Cartledge and James Romm See below (and check back here each week)

– Arrian’s Alexander the Great – In a New Voice Free evening conference/reception in New York City at the NYU Center for Ancient Studies Thursday, Feb 10, 2011 at 6pm. Cohosted by the Reading Odyssey, Inc. Free info and registration here: http://arrian2011.eventbrite.com/

– Arrian’s Alexander the Great reading group Free web/phone-based reading group beginning April 2011 run by the Reading Odyssey. Free info and registration here: http://arrianreading2011.eventbrite.com

————————————————————

Paul Cartledge: Jamie, I’ve been reading the latest book publication by Pierre

Briant, probably the world’s leading ancient Persologist (if there’s

such a word) – technically he’s ‘Professor of the History and

Civilization of the Achaemenid World and the Empire of Alexander the

Great’ at the stellar College de France (founded in 1530 in Paris by

Francois I). The book’s called Alexander the Great and his Empire, and

has been translated for Princeton University Press by another leading

Persologist, emeritus London Professor Amelie Kuhrt. What has struck

me most about it is this: Briant is a leading light in the wave of

scholarship that over the past 20-30 years has sought to re-place the

history of Alexander within the history of the Middle East – to see

him from an eastern rather than western perspective. Which is fair

enough – provided the sources are there to do it. But actually Briant

and those who follow him have a major problem of method – there’s no

Persian equivalent of Herodotus, the world’s first historian properly

so called, who wrote the history of the Graeco-Persian Wars of 490,

480-479 BCE. The Persian Empire (founded c. 550 by Cyrus the Great)

and court produced lots of primary documents – but no historiography.

them from a western perspective also have a problem – there’s no Greek

equivalent of Herodotus for that, either: i.e., though lots of

contemporary Greek writers, including some probably quite good

historians, treated the Alexander story, none of those contemporary

works, not one, survives intact to this day. So it’s very noticeable

that, like any other historian today, Briant for all his brilliance is

forced to rely heavily on the history of

Alexander’s campaigns written by a much much later Greek writer:

Arrian of Nicomedeia (in modern northwest Turkey). Jamie Romm Paul, you’re right to say that we have no Herodotus, and certainly

no Thucydides, for the Alexander era — a situation I lamented in my

editor’s introduction to the new Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of

Alexander. However I also wrote there that we would be much the poorer

if we did not have Arrian either. Granted, Arrian was writing at

second hand — using accounts by two of Alexander’s officers that were

by his time four centuries old — and granted, he had little of the

depth of insight that puts those other two historians in a different

league (he fancied himself a new Xenophon rather than a Herodotus or

Thucydides, as though admitting he was a soldier with some

intelligence and a reasonably good prose style, but not a literary

heavyweight). But the picture he gives us of Alexander is clear,

compelling and filled with fascinating detail, especially in the

military realm. I suppose the central question for all modern readers

is, how reliable is that picture? How much does Arrian cover up the

faults of Alexander — whom he clearly admires — and highlight only the good

points? There are various points of view on this question among modern

scholars — What is yours? PC I belong firmly in the PRO camp, I nail my colours to the mast. One

admittedly rather emotive way of putting that would be to say that

without him we would have no basically reliable narrative to go on –

certainly we couldn’t start from the other surviving narrative sources

and build up an account on the basis of theirs, however much colour –

or alternatively prejudice – they may add. Because obviously Arrian

too was indeed prejudiced: he chose as his two main ‘authorities’, as

you say, two of Alexander’s officers (not any of the writers of

hostile accounts). One of those was a top-drawer Macedonian who’d been

a friend of Alexander’s since boyhood and shared his education by

Aristotle, and who, though not royal by birth, went on to become King

Ptolemy I of Egypt – Pharaoh Ptolemy, indeed, from the native

Egyptians’ point of view. Clearly, Ptolemy’s memoirs will have been to

some extent self-serving, in ways that Arrian perhaps didn’t quite

fully appreciate; on the other hand, few officers and courtiers had

been as intimately associated with Alexander and risen as high in the

command of the empire as Ptolemy had, and what Arrian chiefly used him

for it seems was the nuts and bolts of military campaigning details

which he – as a top-level general himself, who also commanded in Asia

Minor – found plausible and persuasive. His other main source of

choice was a Greek called Aristoboulus – an architect or engineer by

specialization perhaps with a special interest in natural history.

Aristoboulus was sometimes over-generous in his estimate of Alexander

– and underplayed some of his less attractive qualities, such as

excessive alcohol consumption. But the combination of Aristoboulus and

Ptolemy was an intelligent and rational choice by Arrian, especially

given the alternatives… JR ….By which I assume you mean mainly Cleitarchus, the shadowy

Greek who produced the narrative that underlies most of Diodorus,

Quintus Curtius, and Justin, and a handful of even less responsible

writers. This alternate tradition dramatized the Alexander story in

highly diverting ways, but took far less trouble than Arrian did over

accuracy. The gap between them is not as wide perhaps as between

modern tabloid and broadsheet newspapers, but the analogy applies, I

think. My main concerns about Arrian arise when he omits an incident

altogether that the Vulgate sources report — For example, Alexander’s

mass execution of Tyrian civilians after the siege of Tyre. In the

Landmark Arrian I mostly noted these divergences without arriving at a

verdict. We could spend days discussing them on a case-by-case basis,

but let me ask you what your general principles are, before we

conclude this segment of our discussion. When the Vulgate sources

attribute an atrocity to Alexander and Arrian omits it, whom should we

believe? PC Your concerns are entirely justified. Whereas the so-called

‘Vulgate’ tradition of Alexander-historiography that ste

ms from the

contemporary but non-participant Greek Cleitarchus (based in Ptolemy’s

Alexandria!) tends to exaggerate the more lurid and negative aspects

of Alexander’s career, the ‘official’ tradition represented by Arrian

tends to go in the opposite direction, palliating the unpalatable. The

example you select is very well chosen indeed. You call it a ‘mass execution of Tyrian civilians’ – but a source

favourable to Alexander could surely have presented it rather as an

exemplary massacre, in much the same way as the total destruction of

Greek Thebes in 335 could have been presented as exemplary: that is,

designed to prevent a repetition of a kind of resistance to his

project that Alexander had found both unjustifiable and exceptionally

annoying. Why then did Arrian not mention the Tyrian massacre, whereas

he had not merely mentioned but given exceptional and quite negative

weight to the destruction of Thebes as an unmitigated ‘disaster’? Was

it because the Tyrian massacre had not actually happened but was an

invention of a tradition hostile to Alexander? Or was it because

Arrian too thought it was the not wholly rational action of a man

excessively motivated by wounded personal pride and uncontrollable

desire for revenge and therefore should be suppressed? (There is an

exact parallel here to the accounts of the siege of Gaza that followed

soon after that of Tyre: the Vulgate source Quintus Curtius describes

a horrific quasi-Homeric revenge that Alexander allegedly took upon

Gaza’s pro-Persian Arab commander Batis, whereas Arrian merely says

Alexander sold the women and children of Gaza into slavery and

repopulated the city as a fortress with nearby tribespeople – no

mention of the fate of Batis). Well, Arrian as mentioned could present Alexander’s behaviour quite

negatively in regard to Greek Thebes, and he seems to have shared a

widespread view that success went to Alexander’s head leading him into

increasingly megalomaniac and irrational actions, so in principle I

don’t think Arrian would have had to suppress the alleged massacre at

Tyre in order to save (his own view of) Alexander’s good reputation.

On the other hand, I myself find the idea of an exemplary massacre of

Tyrian civilians quite plausible, as I pointed out in my 2004 book on

Alexander. So it’s possible Arrian just didn’t find it worth recording

– or (more likely) didn’t find it mentioned in his two main

‘authorities’., Ptolemy and Aristoboulus. A case of biassed reporting,

then, but not necessarily the imposition of Arrian’s own direct bias? (The Alexander Series will now take a hiatus for the winter holidays.

Happy New Year to all!)

Alexander the Great Discussion Series Part 2

Interested in Alexander the Great? Join us for:

– Weekly dialogue between historians Paul Cartledge (PC) and James Romm (JR)

See below for the second dialogue (and check back here each week). First dialogue is here.

– Arrian’s Alexander the Great – In a New Voice

Free evening conference/reception in New York City at the NYU Center for Ancient Studies Thursday, Feb 10, 2011 at 6pm. Cohosted by the Reading Odyssey, Inc.

– Arrian’s Alexander the Great reading group

Free web/phone-based reading group beginning April 2011 run by the Reading Odyssey

Did Alexander take part in a plot to murder his father?

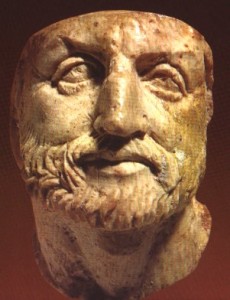

JR: Paul, it’s surprising to me how many historians in recent years have expressed suspicions that Alexander the Great was guilty of conspiracy to commit patricide. The stabbing of Alexander’s father Philip in 336 B.C. was done by Pausanias, a resentful courtier and jilted lover, but he may of course have been put up to the job by others, and he was killed before he could be questioned. In antiquity there were rumors that Olympias, Philip’s third wife, had set the assassination plot in motion, but barely a whisper about Alexander’s involvement. Certainly there has never been any evidence to implicate Alexander, so modern suspicions are pure speculation, aren’t they? Or rather, inferences based on what historians assume about Alexander’s character and motives? PC: Jamie, it does look surprising at first sight, I agree. But let me put to you the following scenario, and I’d ask you to consider it from the point of view of the Roman lawyers’ question ‘cui bono?’ At the time of Philip’s assassination he had already begun his Asiatic campaign – the advance bridgehead force was already ensconced in Asia Minor (northwestern Turkey today). But where was Alexander? Not with that bridgehead force. Nor did Philip have any plans for Alexander to join it. He was going to leave his son and heir behind in Macedonia, as he had done once before, as Regent of his by now very extensive Greek kingdom.Photo: Philip of Macedon

JR: But is it fair to indict a man for murder simply because he stood to gain by the death of the victim? On that reasoning, we could equally well accuse the Persian king Darius III (as Alexander indeed did), or any one of a few thousand Athenians. Ancient writers were certainly willing to charge dynastic rivals with murder on slim evidence — certainly the Romans did this every time a member of the Julio-Claudian family died — but it is interesting that none of them charged Alexander with patricide.

PC: You are quite right that there has never been any good positive historical evidence to implicate Alexander in the assassination, so that modern suspicions must be pure (or rather impure) speculation. But I suggest that such speculation is at least well informed speculation, based as it is both – as above – on the known prior circumstances of Macedonian dynasticpolitics (the 390s were an especially bloody passage for Macedonian royalty …) and then also, as you say, on inferences based on what historians assume about Alexander’s character and motives. For if anything seems to me to be a likely inference from those, it is that Alexander will not have been well pleased to have been left out of the Asiatic campaign altogether. Which is where my Roman lawyer’s question comes in. Cui Bono? means literally ‘for whom [is it/was it/will it be] a good thing [advantageous]’? In other words, in this particular case (pun intended), to whose advantage above all others would it have been to have Philip assassinated? Answer: Alexander. That’s not the same, anything like, as saying that he was- or ‘must have been’ – guilty of putting Pausanias up to it. But it is the same as saying that, in consequentialist terms, Alexander had very good reasons to be not at all unhappy with the outcome. JR: I see your point, but wouldn’t it also have been to Alexander’s advantage to let Philip go ahead and invade Asia, on the assumption that a greatly enlarged empire would pass to him in the end? After all, he was Philip’s son and heir, and Philip couldn’t live forever. Indeed, Alexander might have figured that some Persian cavalryman would finish his father off and do the job for him, if we assume that he even wanted the job done. PC: Well, Alexander was certainly Philip’s oldest legitimate son, but the year before, in 337, he had taken as his seventh (sic) and last consort a noble Macedonian Greek woman, from a family that was by no means on good terms with Alexander, and with whom he was planning to have a son, the first of his sons who would be all-Macedonian (Alexander’s mother Olympias was Greek but not a Macedonian). This marriage had caused Alexander great grief, and he had behaved very badly indeed over it – with surely the at least tacit approval of his mother, who had long been estranged from Philip and who knew all about the murderous nature of Macedonian dynastic politics. For if Philip’s new wife were to bear him a healthy son – as she soon did – and that son were to grow to maturity before Philip’s death, Alexander would without question have been bypassed for the succession to the Macedonian throne, and Olympias’s role in life and probably also her life would have been abruptly terminated. JR: OK, I’m satisfied that Alexander had a motive, but let’s talk means for a moment. The assassin who struck Philip down was a guardsman named Pausanias, supposedly acting out of jealousy — he was formerly Philip’s lover, since jilted — and injured pride. Why would Alexander use an agent to do the deed, someone who might rat the conspirators out, or botch the job, or blab afterward under torture? Pausanias was conveniently killed by security forces as he tied to make his escape from the scene of the assassination; but would Alexander have risked that something might go wrong and his plot would be uncovered? Couldn’t he have done the murder in a more risk-free way by doing it himself — presumably he had lots of opportunities to stab or poison Philip without being detected? PC: The killing of Pausanias immediately after the assassination does seem a trifle – er – suspicious, does it not? i.e., my suspicious mind immediately suspects that whoever put Pausanias up to it (perhaps promising him some promotion or other favour from the new boss?) also made very sure that he couldn’t blab. Poison was never a sure method – and the assassination of Philip at the celebration of the marriage of Philip and Olympias’s daughter Cleopatra (Alexander’s full sister) to Olympias’s brother was a brilliantly public, political act, almost a coup in itself. JR: Well, I’m more inclined to give Alexander the benefit of the doubt (I would have said he’s innocent until proven guilty, but proof in this case — as in most of the Alexander matters we will be discussing — is out of the question). I agree though there’s plenty of grounds for suspicion!

Herodotus Books 4 & 5 Discussion Questions

Alexander the Great discussion series – part 1

Interested in Alexander the Great? Join us for:

– Weekly dialogue between historians Paul Cartledge and James Romm

See below for the first dialogue (and check back here each week)

– Arrian’s Alexander the Great – In a New Voice

Free evening conference/reception in New York City at the NYU Center for Ancient Studies Thursday, Feb 10, 2011 at 6pm. Cohosted by the Reading Odyssey, Inc.

– Arrian’s Alexeander the Great reading group

Free web/phone-based reading group beginning April 2011 run by the Reading Odyssey

– – –

Why was Alexander ‘great’?

First in a series of weekly blog conversations between historians James Romm [JR] and Paul A. Cartledge [PAC], editor and introduction-author of the new Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, just published by Pantheon under series editor Robert Strassler.

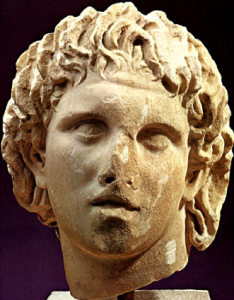

JR: Paul, there are only a few people in history who are universally known as “the Great,” and Alexander of Macedon, who reigned and conquered much of the known world between 336 and 323 B.C., probably tops the list. The word “great” in this context, to my mind, is always positive — implying both that Alexander’s achievements were huge in scale, and that his nature was heroic and awe-inspiring. The question many in the modern world might ask, however, is: Do these two things go hand in hand? Perhaps in the scale of his achievements Alexander was Great, but in his nature Terrible — or perhaps even Terrible in both. So as you and I begin this ten-part dialogue on the controversial figure of Alexander (a conversation made more timely by the recent release of Pantheon’s The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander), maybe it makes sense to ask: Does the appellation “the Great” still make sense for Alexander? Or is it an outdated holdover from an age when conquest and military expansion were more admired than they are now?

PAC: Jamie, I remember a (now very) senior Oxford colleague long ago telling me that all ‘great’ men were by definition bad men… Well, that may be so, but we historians shouldn’t primarily be concerned with our subjects’ morals, but rather with how and why they did what they did, and with what consequences, including among those our current appreciation of their historical significance. Whatever may be thought of Alexander’s morals, there’s no denying that he matters hugely – and always has so mattered, at least from the moment he was acclaimed king of the state of Macedon (which controlled ancient Macedonia – and much else), in the summer of 356 BCE, when he was barely 20. Very few historical actors have been called ‘the Great’, and Alexander is one of only two known to me (I stand to be corrected …) who have had that title incorporated in their very name: Megalexandros in modern Greek – the other is Charlemagne (‘Karl der Grosse’ in German, crowned Holy Roman Emperor at Aachen on Christmas Day, AD 800). Shakespeare has a character (in Twelfth Night) claim that some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them – I doubt myself that the first member of that trilogy makes any real historical sense, but Alexander’s parents, King Philip II and Olympias, were certainly memorable, and their extremely fraught union decisively shaped his first 20 years at least. But by themselves neither they nor his teaching by Aristotle when he was 13, nor any other aspect of his upbringing and background in that corner of northeastern Greece could by themselves account for Alexander’s truly astonishing 13-year reign (336 – 323 BCE). In the succeeding exchanges you and I will be re-examining all sorts of aspects of Alexander’s career, personality and achievement. Here let me kick off with what I consider to be unarguably an argument in favour of his being called ‘the Great’, regardless of what side one happens to be on in any of the many other major controversies that still surround this larger-than-life figure. He was, as it’s been nicely put, a military Midas: as a general – off as well as on the battlefield, in strategy as well as tactics – pretty much everything he touched turned to gold, so long that is as he was pursuing strictly military objectives, whether defeating an enemy, or conquering and holding a territory. He was never defeated in a pitched battle, and in siege or guerrilla operations he suffered only relatively slight reverses at worst. This is not to say he never made a mistake, leading his men as he did over thousands of kilometres through the most formidable terrain for over a decade nonstop. But those mistakes never added up to an outright defeat. ‘Invincible’ the Delphic priestess had allegedly declared him in advance of his campaigning in Asia, invincible he proved. Death alone (by whatever means…) at Babylon in early June 323 BCE proved him literally mortal. Of course, if you happen to be a pacifist by conviction, you probably hate all that Alexander stood for as well as what he did in war, but, if the premise of war be granted, he was surely a formidably great generalissimo. JR: Paul, Your last point raises a question to which I’m afraid I don’t know the answer: When did Alexander first become called “the Great,” and by whom? I would imagine it was the Romans, with their great reverence for military prowess, that awarded him the honor. I would think that the Greeks, who had very mixed and often adverse responses to Alexander — a topic we’ll be discussing in more depth in coming weeks — would not have called him Great, though their were some Greeks of the Roman Empire who very much admired him. Among these was Arrian, a Greek writer and intellectual who became a top administrator in the Roman empire, and who wrote one of the most important accounts of Alexander that survives from antiquity: The Anabasis, translated “Campaigns of Alexander” in the new Landmark edition. PAC: Jamie, it seems that the earliest certain surviving reference to Alexander as ‘Alexander the Great’ is in a play by the Roman New Comedy author Plautus (flourished c. 200 BCE), whose plays were based, often very closely, on earlier Greek originals, so we can confidently (I think) say – it was at some time before 200 BCE! (This site – http://pothos.org/forum/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=2311&start=0 – contains some relevant stuff, along with a lot of irrelevance.) But I would at once add that in itself the title doesn’t matter all that much: what does I think matter a lot is how he was perceived by, on the one hand, the movers and shakers of the immediate post-Alexander Greek world, and, on the other, by ‘ordinary’ Greeks of that same ‘Hellenistic’ (as we scholars know it) world. The former group, that is the rival kings and dynasts and would-be kings and dynasts known collectively as the ‘Successors’ and ‘Epigones’ who slugged it out for well over a generation (323-281 BCE) all to a man (re)presented themselves as Alexander-clones. The latter group included many Greeks living in Asia Minor, who had been liberated from alien barbarian Persian domination by Alexander, and who worshipped him as a god. Without any compulsion, it would seem. You ask whether I might add something about the topics we’re going to go on to discuss in this exchange. With pleasure – here are some possible topics we could argue the toss over: Did Alexander participate in the murder of his father? How good a historian was Arrian? Why did so many Greeks hate Alexander – whereas others (literally) worshipped him? Was Alexander as great a general as he’s usually cracked up to be? Was Alexander a religious fanatic? How genuine was Alexander’s Hellenism (love and promotion of Greek culture)? What really was Alexander’s relationship with his right-hand man

Hephaestion? or/and What did Alexander really think of women? How genuinely Asian was Alexander’s style of kingship? Who or What killed Alexander? What was/is Alexander’s Legacy – what has he done for Us?

Herodotus Books 2 & 3 Conference Call (Bruce’s Group)

Here’s the audio recording for the Herodotus Books 2 & 3 call for Bruce’s group. Listen online or download the mp3 file and listen to it as a podcast on your iPod (or Zune!).

Herodotus Books 2 & 3 Conference call (Andre’s group)

Herodotus Books 2 & 3 Discussion Questions

Dear fellow Herodotus readers,

Happy belated Thanksgiving to you all. I hope your reading is coming along well. Here are the discussion questions again for you to ponder as we get ready for our next discussion scheduled for Monday December 6 @8pm EST. Happy reading!

Andre Stipanovic

1. Book 2 – Consider this remark: “As Herodotus introduces his long digression on Egypt with a reference to the conquest of the Greeks (c. I. 2), so he skillfully concludes with a similar reference.” (How & Wells, p. 256)

How relevant is this comment to the Persians’ eventual invasion of Greece? Even with a satisfactory observation, one may still be wondering ‘what does Book 2 have to do with the Persian invasion of Greece?’ Thoughts?

2. Let’s look at the claim of Herodotus’ Hellenocentric point of view. What do Herodotus’ observations tell about Herodotus as a Greek? Are his observations an attempt to re-define Egypt according to Greek culture? or is Herodotus too much influenced by Egyptian culture to make accurate statements in his History?

3. Book 3 – The rise and fall of Cambyses – How does Herodotus measure the sanity of Cambyses? How does Cambyses take advice and counsel in comparison with his precedessor Cyrus? What does Herodotus mean by “custom is king of all” (3.38.4)?

4. Book 3 – The rise of Darius – How should we view the transfer of power from Cambyses to Darius? Is this a monarchy? despotism? tyranny? oligarchy?

5. Book 3 – Darius and Democedes (3.129) – What does this story show about Darius’ encounter with the Greeks? What does this story have to do with the story that ends Book 3, i.e. Zopyrus and the fall of Babylonia to Darius?

Herodotus Book One Reader Call, 11/17/10 (Bruce’s group)

Dear fellow readers,

Thanks for your participation and questions last night during our discussion of Book I. It was a great call, I thought, and we learned a lot from each other about the roles of fate and prophecy in the stories of Croesus, the Median Kings and the rise (and fall) of Cyrus. Alan also did some terrific research proving just how inaccurate Herodotus was in his measure of the walls of Babylon. Fifty percent more surface area than the Great Wall of China? I don’t think so!

You can listen to the call by clicking the play button above.

Study guide questions for Books 2 & 3 are below, which we will use as discussion anchor points on our next conference call scheduled for Monday December 6. Until then, share your thoughts and questions with us on email and I look forward to our next discussion.

Sincerely,

Bruce

Books 2 & 3 Discussion Questions

1. Book 2 – Consider this remark: “As Herodotus introduces his long digression on Egypt with a reference to the conquest of the Greeks (c. I. 2), so he skillfully concludes with a similar reference.” (How & Wells, p. 256)

How relevant is this comment to the Persians’ eventual invasion of Greece? Even with a satisfactory observation, one may still be wondering ‘what does Book 2 have to do with the Persian invasion of Greece?’ Thoughts?

2. Let’s look at the claim of Herodotus’ Hellenocentric point of view. What do Herodotus’ observations tell about Herodotus as a Greek? Are his observations an attempt to re-define Egypt according to Greek culture? or is Herodotus too much influenced by Egyptian culture to make accurate statements in his History?

3. Book 3 – The rise and fall of Cambyses – How does Herodotus measure the sanity of Cambyses? How does Cambyses take advice and counsel in comparison with his precedessor Cyrus? What does Herodotus mean by “custom is king of all” (3.38.4)?

4. Book 3 – The rise of Darius – How should we view the transfer of power from Cambyses to Darius? Is this a monarchy? despotism? tyranny? oligarchy?

5. Book 3 – Darius and Democedes (3.129) – What does this story show about Darius’ encounter with the Greeks? What does this story have to do with the story that ends Book 3, i.e. Zopyrus and the fall of Babylonia to Darius?

Herodotus Book One Call, 11/15/10 (Andre’s group)

Dear fellow Herodotus readers,

Thanks for your participation and questions last night during our discussion of Book I (soon to be attached above). Because of your comments, I am looking at Herodotus in a different way. Look for study guide questions for Books 2 & 3 below, which we will use as discussion anchor points on our next conference call scheduled for Monday December 6. Until then, share your thoughts and questions with us on email and I look forward to our next discussion.

Sincerely,

Andre

Books 2 & 3 Discussion Questions

1. Book 2 – Consider this remark: “As Herodotus introduces his long digression on Egypt with a reference to the conquest of the Greeks (c. I. 2), so he skillfully concludes with a similar reference.” (How & Wells, p. 256)

How relevant is this comment to the Persians’ eventual invasion of Greece? Even with a satisfactory observation, one may still be wondering ‘what does Book 2 have to do with the Persian invasion of Greece?’ Thoughts?

2. Let’s look at the claim of Herodotus’ Hellenocentric point of view. What do Herodotus’ observations tell about Herodotus as a Greek? Are his observations an attempt to re-define Egypt according to Greek culture? or is Herodotus too much influenced by Egyptian culture to make accurate statements in his History?

3. Book 3 – The rise and fall of Cambyses – How does Herodotus measure the sanity of Cambyses? How does Cambyses take advice and counsel in comparison with his precedessor Cyrus? What does Herodotus mean by “custom is king of all” (3.38.4)?

4. Book 3 – The rise of Darius – How should we view the transfer of power from Cambyses to Darius? Is this a monarchy? despotism? tyranny? oligarchy?

5. Book 3 – Darius and Democedes (3.129) – What does this story show about Darius’ encounter with the Greeks? What does this story have to do with the story that ends Book 3, i.e. Zopyrus and the fall of Babylonia to Darius?